What Was the ACE Study?

Conducted in the late 1990s, the landmark ACE Study is one of the most notable studies to examine the nature and long-term effects of childhood trauma closely. The ACE Study evaluated over 17,000 adults to determine the mental and physical impact on those who faced adversity in their childhood home. Several unexpected and groundbreaking findings emerged from the study, which concluded that the greater the number of adversities adults faced in childhood, the more likely they were to experience mental and physical health problems throughout life.

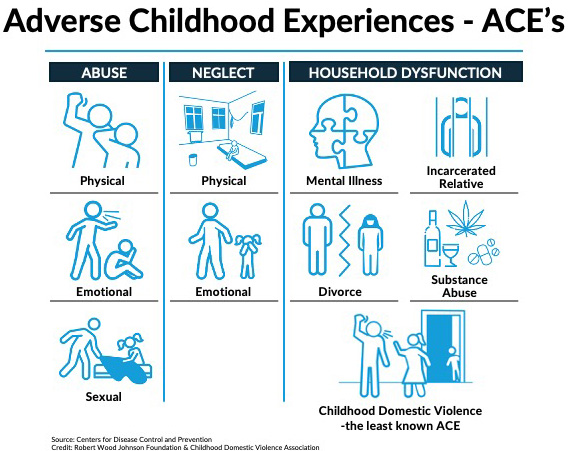

What are ACEs, or Adverse Childhood Experiences?

The ACE Study classified adversities as anything traumatic or stressful, from physical, sexual, and emotional abuse or neglect to witnessing domestic violence or divorce between parents, experiencing family members or relatives going to jail, and living in a household where there was substance abuse. The study revealed the hidden nature of childhood adversity and the silence that surrounds it, while discovering various outcomes that were not anticipated from data previously available because of the lack of awareness and recognition of the full scale impact of childhood trauma. “I thought I would die never having told anyone about my childhood,” one ACE Study participant wrote in their questionnaire.

The Impacts of Childhood Adversity Continue into Adulthood

A remarkable discovery of the study was that childhood adversities affect adults of all backgrounds and are just as common among white, highly educated adults. Since minority children from lower-income families are most prevalent in the welfare system, it was expected that most adults who have reported childhood trauma would be from this background. But the ACE Study found otherwise. It proved that childhood trauma is exceedingly common, with 67% of participants indicating they had faced some significant adversity in childhood.

The study also showed that the 10 key adversities very rarely occur in isolation, and roughly 10.5% of participants had experienced five or more Adverse Childhood Experiences, and that 13% had faced childhood domestic violence, or CDV. It also reaffirmed that childhood adversity has an inter-generational domino effect, because the dire repercussions it causes, such as substance abuse or mental illness, “may make it likelier that the next generation will experience ACEs as well.” If you suspect you may have faced childhood domestic violence, or are unsure, please use our easy, private screening tool.

What are Those Impacts?

Among dire outcomes associated with ACEs in adolescence are an increase in substance abuse and high-risk behavior, but these outcomes often persist into adulthood. There is also a heightened risk of multiple health problems in later life, such as cardiovascular disease, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, suicide attempts, alcohol dependence, marital problems, etc.

“If there is one common thread to many of the preventable diseases we face in the U.S., why are we not paying closer attention?” writes Dr. Dube. This has been a common thread among clinicians in recent years. As the impact of childhood adversity begins to emerge from the shadows and gain more widespread recognition in professional circles, the urgency to address it more proactively is growing.

The good news is that “research also suggests that humans have an innate capacity to adapt and positively transform, even after traumatic and stressful events,” given the right environment and supportive factors to help facilitate this. So the dire predictions can be reversed under the right conditions and with the right intervention strategies.

How Common Are Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)?

Steps to Respond to High ACE Exposure

If your ACE score is high, it doesn’t mean you’re doomed; it means your past deserves attention and care. There are concrete ways to respond:

-

Understand what ACEs affect. High scores are linked to increased risk of physical illness, mental health challenges, and substance use. Knowing this helps you connect the dots between past experiences and current struggles.

-

Learn what’s in your control. While you can’t change your childhood, you can change how you respond to its effects. That includes building supportive relationships, setting boundaries, and developing consistent routines that bring safety and calm.

-

Use tools that work for you. Not everyone connects with traditional talk therapy. Some benefit more from self-guided books, structured programs, group workshops, or worksheets that help process emotions at their own pace.

-

Start where you are. Change doesn’t need to be dramatic to be meaningful. Even small steps, like tracking triggers, naming your feelings, or writing down a few honest thoughts, can start to shift the way you relate to yourself.

-

Stay curious, not judgmental. If you find yourself repeating patterns or feeling stuck, it doesn’t mean you’ve failed. It often means a deeper wound needs attention. That realization is not a setback: it’s a signpost.

These steps are not about fixing what’s “broken.” They’re about responding to what was never your fault with steady, grounded care.

To learn more, read the full article, “How Childhood Trauma Can Affect Mental And Physical Health Into Adulthood” by Shanta R. Dube, Associate Professor at the School of Public Health at Georgia State University, on The Conversation via this link: https://theconversation.com/how-childhood-trauma-can-affect-mental-and-physical-health-into-adulthood-77149