Who do you think of first when you hear the term post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

Do most people think of a combat soldier as a war-hardened veteran? Or do they think of a child who is growing up with domestic violence? Did you know that both the soldier and child can develop Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), producing many of the same symptoms and pitfalls impacting all areas of life with their respective experiences?

The children living with violence face a significant adversity – childhood domestic violence (CDV). And the impacts of CDV can lead to disorders, such as PTSD in childhood. And for many of these children, both will impair their ability to thrive throughout their entire lives without aid.

What Is PTSD and Why It Matters for Children

Before looking further into statistics or comparisons around PTSD, here is a quick definition, provided by the National Institute of Mental Health:

“PTSD is a disorder that develops in some people who have experienced a shocking, scary, or dangerous event. It is natural to feel afraid during and after a traumatic situation. Fear is a part of the body’s ‘fight-or-flight’ response, which helps us to avoid or respond to potential danger.”

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in children can develop after they witness or live through frightening or harmful events, such as domestic violence, abuse, or chronic stress in the home. Unlike occasional fear or sadness, PTSD involves ongoing symptoms that interfere with how a child thinks, feels, and functions.

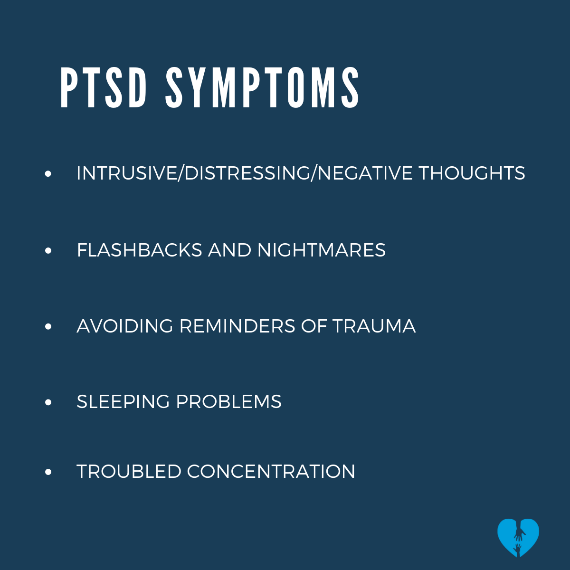

When a child lives with PTSD, they may struggle with recurring nightmares, emotional numbness, difficulty concentrating, or intense fear triggered by reminders of the trauma. These signs often go unnoticed or are mistaken for misbehavior or moodiness.

Why does this matter? PTSD in children can have lasting effects on their brain development, relationships, learning, and mental health. Without support, they may carry patterns of fear, hypervigilance, or low self-worth into adulthood. Early recognition and consistent care—whether through therapy, structured tools, or a stable relationship with a caring adult—can interrupt that cycle.

Understanding what PTSD looks like in children is the first step toward helping them heal. Long-term recovery is possible, especially when adults respond with patience, structure, and tools that meet the child where they are.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Children

|

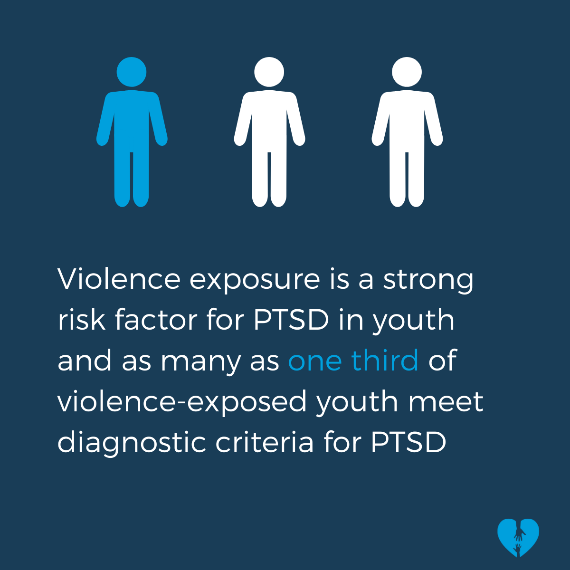

In the U.S., approximately 1 in 6 children have witnessed domestic violence in their lifetimes. More than 1 in 5 have witnessed other assaults in their families. One of the most common psychological responses to violence exposure is PTSD. |

|

|---|

How Common Is PTSD Among Children Exposed to DV

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a serious concern for children who grow up witnessing domestic violence. Research shows that up to one in three children exposed to violence in the home may develop PTSD symptoms. Even when they are not the direct target of abuse, witnessing repeated conflict, yelling, or physical aggression can overwhelm a child’s nervous system and lead to trauma-related responses.

In high-risk environments, such as emergency shelters, studies have found that 20–30% of children meet full diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Many more show partial symptoms—like sleep problems, emotional numbness, irritability, or flashbacks—even if they haven’t been formally diagnosed.

Because PTSD symptoms in children often look different from those in adults, the condition may be overlooked. Instead of describing fear or distress, children may act out, withdraw, or seem overly alert. Recognizing how common PTSD is among kids who witness domestic violence is key to identifying those who need support early on.

With the proper care and attention, children affected by CDV and PTSD can recover and rebuild trust, safety, and emotional regulation over time.

How CDV Changes the Brain and Leads to PTSD

Childhood Domestic Violence (CDV) doesn’t just affect a child emotionally—it alters how their brain develops. When a child is repeatedly exposed to violence between caregivers, their body stays on high alert. This constant stress activates the brain’s survival systems in ways that can have long-lasting effects.

Chronic exposure to fear and conflict can alter the functioning of the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex. These are areas involved in fear responses, memory, and decision-making. Children raised in violent homes often develop heightened startle responses, difficulty regulating emotions, and trouble with concentration—all common signs of trauma-related stress.

Over time, these changes can lead to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in children who witnessed domestic violence. PTSD develops when the brain continues to respond as if danger is present, even after the violence has stopped. Children may experience flashbacks, avoidance, nightmares, and difficulty trusting others.

Understanding how CDV impacts a child’s brain helps explain why their behavior might seem unpredictable or intense. It also emphasizes the importance of early, supportive intervention to mitigate long-term effects and provide the child with a chance to heal in a safer, more stable environment.

Signs a Child May Have PTSD from Witnessing Violence

Children who witness domestic violence may develop symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), even if they were never physically harmed. These signs often appear in subtle or misunderstood ways. Recognizing early warning signs of PTSD in children exposed to violence is key to offering the proper support.

Here are common symptoms:

-

Nightmares or trouble sleeping without a clear cause

-

Avoidance of specific places, people, or situations that remind them of past events

-

Emotional numbness or appearing disconnected from others

-

Frequent outbursts or irritability, sometimes misread as behavioral problems

-

Difficulty concentrating or focusing in school

-

Exaggerated startle response to loud noises or sudden changes

-

Clinginess or separation anxiety, especially in younger children

-

Negative self-talk (“It was my fault,” “I’m bad”) is tied to guilt or shame

These symptoms can persist long after the violence has stopped. In many cases, adults may mistake them for attention-seeking, stubbornness, or mood swings. But when these patterns continue for several weeks or interfere with daily life, they may be signs of PTSD caused by witnessing domestic violence.

If you notice these behaviors, early support—whether through structured tools, safe routines, or trauma-informed care—can make a lasting difference.

Ways to Support a Child with PTSD (Beyond Therapy)

CDV changes the patterns of the brain similarly to the way combat impacts a soldier’s brain. Like the soldier who experiences trauma in wartime, the trauma of CDV increases the risk of chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance abuse.

Children who grow up with domestic violence are more prone to worry, have more fears, and feel more helpless and obsessively. These feelings induce enough toxic stress in the body to change brain structure and cause disorders such as PTSD. Adverse effects may include anxiety, nightmares, depression, withdrawal, and aggression.

|

And although the adult soldier has lived life longer than the child, the effects of PTSD are similar. They, like the children, develop brain patterns that change what they believe and how they would typically respond under less duress. The trauma of war and the trauma of domestic violence both rewire the brain in much the same way. |

Tools That Help Children Manage Trauma at Home

On the flip side of PTSD is post-traumatic growth – it’s the ability to experience positive changes after significant trauma.

It is estimated that 50% – 66% of trauma survivors may experience post-traumatic growth. A key concept is that those who experience this growth not only persevere but also become more resilient. They can also reflect, grow, and shift their perspective.

Although not everyone will sustain post-traumatic growth, the research is improving and growing on how to help both children and adults get a better handle on their lives while living with PTSD. In most cases of PTSD, professional help is needed, but NIH offers up some suggestions on how anyone can provide support.

Children who experience domestic violence have the capacity for remarkable resilience under adversity, though some of these children will develop PTSD. And some will require one or more forms of professional assistance.

PsychCentral.com provides a guideline for caregivers/parents, broken down by age, on how to help children who have developed PTSD.

Fortunately, more studies are being conducted and more awareness is being spread to show the connections of CDV to PTSD, and how it can rewire the brain. The striking comparison of two brains being rewired the same way shows how traumatic CDV is for a child, akin to combat conditions for a soldier.

If these children get the help they need, they will be able to step out of the shadow of CDV and PTSD and grow up to be the thriving adults they are meant to be.