At the Childhood Domestic Violence Association, we believe that language has the power to open doors—to healing, to awareness, and to change. Before transformation can begin – before a conversation, a policy, or a support system—there must be a name.

The term Childhood Domestic Violence (CDV) was first introduced by European researchers to more accurately describe what happens when a person in childhood grows up living with domestic violence. Their insight was significant: this is not something a person in childhood merely sees. It is something they live through. It is not peripheral to their development; it is central to it.

When we encountered this term, we immediately recognized its accuracy and power. It named something that had always been there but was rarely acknowledged, especially in public discourse. At the Childhood Domestic Violence Association, we did not invent this term. But once we came across it, we tested it, similar to the way you would test a ‘new brand’ and it far and away outperformed other available options.

Why Earlier Language Fell Short

For decades, the experience we now call childhood domestic violence was described with terms like “child witness to domestic violence” or “child exposure to intimate partner violence.” These phrases, used across legal, academic, and clinical settings, were never wrong, but they were never enough. From a semantic perspective—the study of meaning in language—they were too long, too clinical, and above all, too passive. The word “witness” implies distance. It suggests that a person in childhood stood on the sidelines and simply observed. But trauma science shows us the opposite. When domestic violence is part of the environment a person grows up in, it becomes part of them—physiologically, emotionally, neurologically. It is not something they witnessed; it is something that happened to them. Witnessing is experiencing.

The Power of Naming

Naming matters. In semantics and psychology alike, naming is a turning point. It takes what is invisible and gives it shape. A powerful parallel is the naming of PTSD. Before post-traumatic stress disorder had a name, those living with it—especially veterans—suffered in silence. They lacked a way to describe what they were experiencing, and society lacked a framework to respond. Once named, PTSD became something real, something shared, something treatable. The same is true for childhood domestic violence. When someone hears the term and realizes, “Yes, that’s what I lived through,” a shift occurs. Confusion turns to clarity. Silence turns into speech. Pain finds a path forward.

Why “Childhood Domestic Violence” or CDV Works

The term childhood domestic violence works in ways earlier labels could not. It is a noun—something fixed and graspable. It’s concise and easy to remember, like PTSD or ADHD. It describes exactly when the experience occurs—in childhood—and what kind of experience it is: violence in the home. It validates that what a person endured during those formative years wasn’t something on the periphery. It was central to their development. It also helps correct a widespread and damaging misperception. Many adults who grow up living with domestic violence during childhood don’t believe they were affected. “I wasn’t hit,” they say. “I just saw it.” But trauma experts agree: the brain and body of a person in childhood respond to chronic stress in the environment, regardless of whether they were physically touched. Domestic violence doesn’t have to land on them to land in them. Naming it childhood domestic violence confirms that this experience has meaning—and that its impact is real.

Not Just a Childhood Issue—A Generational One

Research shows that the best predictor of whether a person will be involved in a domestically violence relationship later in life—as a victim or as a perpetrator—is whether they experienced childhood domestic violence. That makes CDV both a trauma and a predictor. When we name it, we can begin to interrupt the cycle by providing assistance to the adults who were those children who, prior today, did not even know what to call it. That shift in perspective is critical.

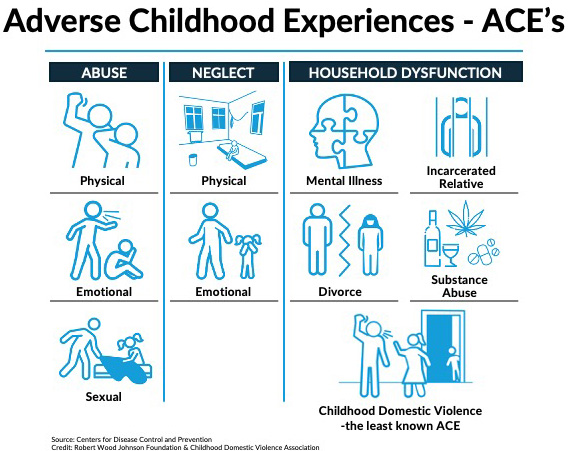

The Least Known ACE

Among the ten recognized Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), Childhood Domestic Violence remains the least known. And yet, it is one of the most pervasive. UNICEF has called it one of the most pervasive human rights challenges of our time. More than 275 million children worldwide are currently experiencing it, and more than twice that number of adults experienced it in their own childhoods—many without ever knowing what to call it. That invisibility stems, in large part, from the absence of accessible language. If we cannot name it, we cannot talk about it. And if we cannot talk about it, we cannot change it. That’s why the use of the term is growing, not just in the United States but internationally. While it first emerged from European research communities, more scholars, practitioners, and advocates around the world are now adopting “Childhood Domestic Violence” to describe this experience. This global consistency in language is a promising step toward shared understanding, collective advocacy, and ultimately, scalable change.

It Begins with a Name

Naming something is not a small act. It is a beginning. As Tony Robbins, who wrote the foreword to the book Invincible, once said: “What’s the first thing you do when you get a dog? You name it. Only then can you teach it to come.” That metaphor, while simple, holds deep truth. When we name something, we create the possibility of relationship. We begin to understand it, work with it, and heal from it. One researcher said it best: “Naming it is intrinsically healing.” We see this every day at the Childhood Domestic Violence Association. When a person realizes there’s a name for what they went through in childhood, a light comes on. A quiet recognition settles in. A sense of relief follows: “I’m not the only one. And this wasn’t my fault.”

Where We Go From Here

Our mission at the Childhood Domestic Violence Association is to help those who experienced Childhood Domestic Violence reach their innate potential. We do this by developing and delivering scalable tools rooted in awareness, education, and empowerment—like Change a Life, our free online training that helps any caring adult learn how to support someone currently living with CDV. But none of our work would be possible without one simple truth: before you can build a future, you must name the past. Childhood Domestic Violence is not just a more accurate term—it is a more powerful one. It gives voice to a silent experience. It creates space for healing. And it reminds each person who lived through it during childhood: this matters. You matter. And you’re not alone. Because naming it is not the end. It’s the beginning.